It’s always difficult to capture in a few words the changing state of modern nutrition, the implications of new scientific findings, the wisdom of calls for change to dietary advice and the conservative response. Yet Professor Jennie Brand-Miller from the University of Sydney managed to do it at a recent food labelling conference in a presentation titled ‘Old nutrition, new nutrition’.

Old nutrition

Brand-Miller began by stating: The old nutrition goes like this ….

- Foods can be dissected into macronutrients

- Saturated fat is the main dietary risk factor for cardiovascular disease

- A low fat diet is best for prevention of obesity, diabetes and cardiovascular disease

- “Eat a diet that is low in fat and high in complex carbohydrate”

- “Eat plenty of cereals, breads, rice, pasta and noodles, preferably wholegrain”

And then she took old nutrition apart, highlighting how the nutrition landscape had changed over the past decade or so:

• Large, long-term, randomised controlled trials had showed low fat dietary advice did not prevent heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes, breast cancer or colon cancer.

• The prevalence of obesity and type 2 diabetes had continued to increase, despite the adoption of lower fat diets in Australia and the United States.

• In relation to heart disease risk, some carbohydrates were worse than saturated fat. In particular, high glycaemic index carbohydrates were linked to higher risk of cardiovascular disease, as well as higher risk for diabetes and some cancers.

• Higher fat, Mediterranean-style diets produced better weight control and cardiovascular outcomes than low fat diets.

• When compared head-to-head in high quality randomised controlled trials, energy-dense, high protein, very low carbohydrate diets were associated with faster weight loss and better cardiovascular risk factors than low fat diets.

• Low glycaemic index/low glycemic load diets were associated with improved diabetes control, prevention of weight re-gain and reduced risk of type 2 diabetes.

Ouch! That hurt!

In explaining the shortcomings of the old nutrition and the benefits of alternative approaches Brand-Miller argued that foods’ effects on postprandial glycaemia and insulinemia were central. Here was a unifying mechanism that encompassed effects on blood lipids, oxidative stress, markers of inflammation and, importantly, satiation and appetite control.

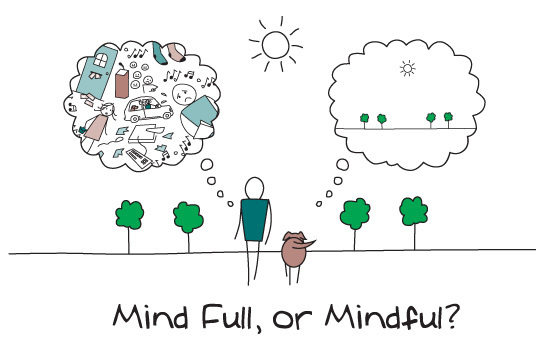

Image: source

New nutrition

Warming to her task Brand-Miller continued: So the new nutrition goes something like this …

- Low fat dietary advice has been unhelpful. It is consistently associated with weight re-gain. It does not reduce the risk of chronic disease.

- We should pay more attention to protein.

- We should pay more attention to the quality of carbohydrate sources. We need to swap high GI carbohydrate for low GI.

- Unlike Americans, Australians don’t eat too much sugar.

- There is a range of healthy macronutrient ratios.

- High fat Mediterranean diets, higher protein diets and low GI diets are all helpful .

Brand-Miller argued that this advice offers flexibility and moderation; it accommodates cultural and ethnic differences; and it is behaviourally more sustainable. She stated that some authorities are already embracing the new nutrition, including the Institute of Medicine and the Joslin Diabetes Clinic in the United States, which have begun to recommend lower carbohydrate and higher protein intakes.

Image: source

Food labelling: new system, old nutrition

Most dietitians and nutritionists would be aware that a new front-of-pack food labelling system is to be introduced in Australia. Similar to the energy star rating system on electrical goods, the easy-to-interpret labels are intended to help the general public quickly assess the nutritional value of foods and identify healthier choices. Of course, whether the scheme actually provides meaningful guidance to the consumers will depend on the criteria used to assess the nutritional quality of foods.

Brand-Miller argued that the algorithm underpinning the new star system is based on old nutrition, highlighted by the focus on energy, fat, salt and sugar. She reeled off a string of anomalies: lentils and liquorice have the same energy density; nuts are more energy dense than French fries; dried fruit is full of sugar; and soft drinks are low in sodium.

In an aside, Brand-Miller said if breast milk were sold in the dairy compartment of the supermarket it would be docked a star because of its sugar content – human milk has the highest sugar content of any mammalian milk. Isn’t it interesting how Mother Nature knows how to ensure that infants drink their milk and thrive but humans are criticised when they use the same strategy with older children, sweetening milk to improve its palatability?

Surprisingly, in spite of embracing old nutrition, the star food labelling system virtually ignores micronutrients. Isn’t the provision of essential nutrients is the fundamental nutritional role of food? Brand-Miller argued that any star system should use Adam Drewnowski’s nutritional quality index as an essential component.

Starch: goodness by default

For Brand-Miller, a major concern about the proposed food labelling system is the healthiness afforded to starch, which is achieved by default i.e. by what it’s not – fat and sugars. The idea that starch is protective relative to fat, or even saturated fat, is prehistoric. Pooled data from 11 large cohort studies shows that carbohydrate and saturated fat pose the same risk for coronary heart disease. In 2010, a European study was published showing that high GI carbohydrates posed greater risk than saturated fat, reinforcing the concern about glycaemic load flowing from studies in the United States. Many starchy foods, even some wholegrains, have high GIs. Seriously, how can a food labelling system encourage less saturated fat and more high GI starchy foods? It’s as logical as recommending more saturated fat and less high GI foods.

Rating starch above sugars is also fraught. In a previous post I highlighted that the relative amounts of sugar and starch in Australian breakfast cereals are unrelated to nutrient density, energy density or glycaemic index. In other words, in these starch-based foods the amount of sugar present is not related to any property or mechanism that might conceivably affect health. Yet the new star food labelling system will separate breakfast cereals on the basis of sugar – healthy eating advice that won’t affect health. Sounds a bit like the old nutrition, doesn’t it?

Policy failure

We would have had more insight into these issues if the National Health & Medical Research Council had commissioned systematic literature reviews into saturated fat and glycaemic index/load for the latest dietary guidelines, but it did not. As far as I know the NHMRC has never systematically reviewed the evidence relating to GI in the 30 years that the concept has been around. With the proposed food labelling system we are now paying the price for this policy failure.

If the responsible health authorities refuse to even consider some of the scientific literature dietary advice will never change. Perhaps that’s the idea.

Image: source

thanks for the blog post Bill – we still have so much more to learn. I keep saying that nutrition is such a young science!

Four years ago, I was diagnosed with T2 diabetes. The first thing I did was go on a low fat, low calorie diet to lose weight. I lost 30 kgs and stabilized my weight, but the blood sugars started rising again. So I did some research. I’m a physicist by training, so I can kid myself that I know how to find things out, evaluate and analyse them, and form some logical conclusions. Essentially, I came to the same conclusion as Professor Jennie Brand-Miller.

So I can now continue on my lowish carbs, mixed protein, saturated/unsaturated mix of fats, low GI, high veg diet which has given me weight control, and lowered my blood sugar, blood pressure, chloresterol,…, but do so without the associated guilt and criticism by nutritionists and dietitians?

Fantastic, concise, clear summary. I’ve bookmarked this for future reference!

Great article, having just completed my studies in dietetics would be interested in knowing what constitutes a lower carb, lower fat and higher protein diet? Would it be just in saying that consuming 45% of energy from carbohydrates is considered low? Same for fat with 20% and high protein being 25% of total energy intake using the AMDR’s?

So for a person consuming 8700 kJ per day this would equate to: 245g of carbs, 47g of fat (remembering that this should be predominately mono- and polyunsaturated) and 128g of protein per day.

I look forward to your response

Hello Chris

What constitutes high/low fat or carbohydrate may depend on when you first studied nutrition. For me, it was the late 1970s and I was taught that a balanced diet had 40% of calories from fat and 40% from carbohydrate. Then the low fat era began, ending up with recommended fat intakes of 20-35% E and correspondingly high carbohydrate intakes. Now the pendulum is starting to swing back. For example, in the Diogenes study (diet and weight re-gain) the fat content was held constant at 36% of calories.

Thinking in terms of high fat/low fat or high carb/low carb is “old nutrition”. The quality of fat-rich foods and the quality carbohydrate-rich foods is key. If quality is good, the relative amounts of fat and carbohydrate don’t really matter. There is nothing wrong with eating 40% of calories as fat, if the fat quality is good. It’s the Mediterranean Diet approach – proven beneficial.

Similarly, high carbohydrate intake is OK if the carbohydrate quality is good. However, most people who eat lots of carbohydrate actually eat quite poor diets, with high glycaemic load and plenty of empty calories.

Protein tends to get forgotten but the evidence is mounting that a bit more protein in the diet and less fat+carbohydrate may be a good thing, especially for weight management.

Regards, Bill

Hi Bill

As Editor of Australasian Leisure Management, I have been writing on fitness, nutrition, obesity, wellness etc for the past ten years. Fitness magazines are filled with articles on the benefits of increasing the amount of protein, vegetables and fats ie olive oil. Carbohydrates ie oats and some fruits ie all the berries are also highly recommended. This dietary advice has proven successful for a large number of people having diverse lifestyles and backgrounds.

I agree with you “Protein tends to get forgotten but the evidence is mounting that a bit more protein in the diet and less fat+carbohydrate may be a good thing, especially for weight management.”

What I also find disturbing is the amount of money spent on obesity research which often results in regurgitated information that ultimately isn’t proving to be effective in reducing the actual levels of obesity!

Hi Karen

I think many nutrition professionals are weighed down by what makes sense to them. The whole focus on lowering fat intake to address obesity makes sense; it just doesn’t work. Perhaps one day a greater focus on protein will make sense.

Unfortunately, it takes about 10 years for new scientific findings to find their way into clinical practice, partly because of professionals clinging onto their beliefs and partly because they don’t keep up with scientific developments. Through your publication, you can help. Regards, Bill

Hi Bill,

I have worked with the algorithm underpinning the star system and I must say, I am utterly unconvinced by it.

Processed muesli bars were coming out with 4 stars due to the massive weighting on fibre

Fresh salmon got the same amount of stars as meat burger patties!

Just a couple of the anomalies I came across. I totally agree with you in that nutrient density should underpin any national FOP labelling system. I think this system has the potential to confuse people even more.

Hi Emma

I’m not involved with the development of the star labelling system I so don’t have any recent solid information on it. However, anecdotal reports are that ‘it wasn’t working’ and more development was required.

Like you, I would like to see some work getting it right conceptually. If the provision of essential nutrients is the fundamental nutritional role of food, how can you ignore nutrient density? Sure, put some weighting on fibre, but let’s not forget than fibre may prevent disease in 30 or 40 years time. Thiamin prevents disease in the next few months. We take essential nutrients for granted. Nutritionists should take a look at the state of those poor people escaping from that enclave in Damascus after nine months of nutritional deprivation, reduced to eating grass to survive. They had plenty of fibre!

Regards, Bill

While I acknowledge that the star rating system has some flaws, there is good reason for not incorporating micronutrients. As soon as micronutrients start getting stars, we get boiled lollies, chocolate bars and soft drinks fortified with vitamins or minerals and improving their health rating. This would not be a step forward. It is also worth noting that Jenny Brand-Millers speech at the food labelling conference did not go uncontested, and not only by those who fear change and cling to the ‘old nutrition’ either. There is genuine scientific debate about the credibility of many of her claims.