At last a trial of monounsaturated-rich Mediterranean diets for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease has been published and the results are impressive. The missing piece of the puzzle is now in place. Mediterranean-type diets, moderate in total fat but enriched with unsaturated fats, are now the preferred model for healthy diets. But will nutritionists pay any attention or cling to the low fat dogma for a little longer?

Although advice to eat less saturated fat has been a fixture in Dietary Guidelines for three decades, the last four years have seen a spirited debate about what should take its place in healthy diets. As saturated fat is a macronutrient, one can’t just ‘eat less saturated fat’ and maintain energy balance. Saturated fat needs to be replaced by something else, such as carbohydrate or unsaturated fats. Carbohydrate is now considered a poor replacement for saturated fat as these two macronutrients confer the same risk for heart disease. This leaves mono- and polyunsaturated fats as the better options to replace saturated fat, but which of these should be preferred?

Until recently, the evidence for polyunsaturates was stronger than that for monounsaturates. Both classes of unsaturated fats have beneficial effects on blood lipids and both appear to be protective against heart disease in observational studies. But the big difference in the evidence bases was that there have been many trials involving the replacement of saturated fat with polyunsaturated fat for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and the better trials have recently been subject to meta-analysis, providing a rare degree of confidence in this dietary recommendation.

In contrast, there had not been a single primary prevention trial of mono-rich diets, until now.

The PREDIMED Study

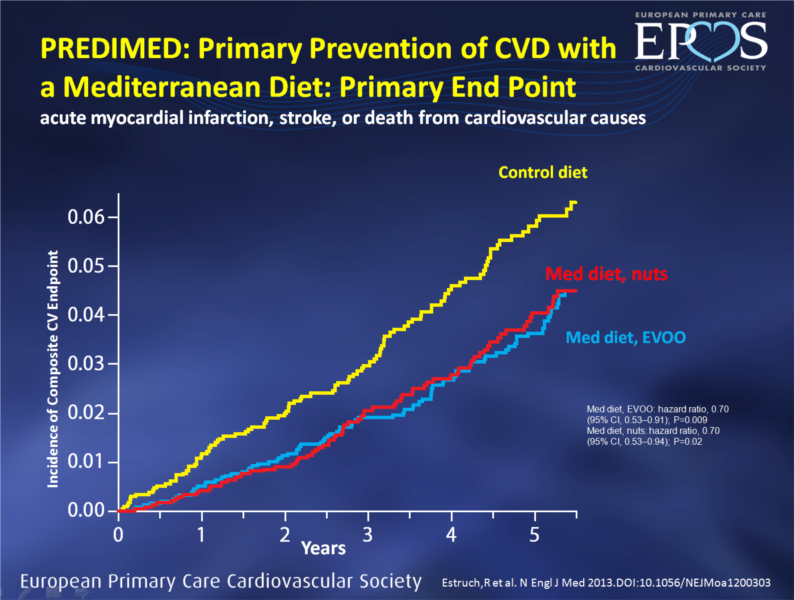

February this year saw the publication of the results of the PREDIMED Study, a randomised controlled trial for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease using Mediterranean diets. This multi-centre trial conducted in Spain assigned subjects who were at high risk of cardiovascular disease to one of three diets – a control diet low in fat, or one of two Mediterranean diets enriched with either extra virgin olive oil or nuts. Energy intake was not restricted and exercise was not advocated.

Image: source

After 4.8 years, both Mediterranean diets significantly lowered the rate of the primary end point (myocardial infarction, stroke and death from cardiovascular causes) by about 30 per cent relative to the low fat control diet. In those following the Mediterranean diets, favourable trends were seen for both myocardial infarction and stroke. No adverse diet-related effects were reported.

These exciting findings stand in contrast to those of the Women’s Health Initiative, a huge US randomised controlled trial for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease using a low fat diet which showed no benefit whatsoever. Thus PREDIMED provides a strong endorsement of the Mediterranean diet as the basis for healthy diets for the prevention of cardiovascular disease. The Mediterranean diets were also associated with lower risk for diabetes (see my earlier post).

Monos or polys?

In relation to the polys or monos question, the olive oil arm of PREDIMED was richer in monounsaturates than the nuts arm, which included poly-rich walnuts. The key point is that both diets were protective and equally so. Based on these findings it would appear that there is little to be gained from choosing polys over monos or vice versa – both appear to be good substitutes for saturated fat (and carbohydrate for that matter). Let’s confine the monos versus polys argument to history.

In considering the results of PREDIMED it’s important to bear in mind that this is a whole-diet study and that it is difficult to attribute the benefit to just one aspect of the diet. The foods consumed as part of the Mediterranean diets differed from the control diet in several ways – legume and fish intake, as well as nuts and olive oil intake, were higher in the Mediterranean diets. So it’s a package deal – the benefit is associated with the whole diet.

The challenge for nutritionists

A generation of nutritionists (including me) was educated to think that a healthy diet is a low fat diet and the results of PREDIMED, and the Women’s Health Initiative before it, provide further evidence that this is not the case. The PREDIMED investigators provided high fat foods to their subjects to provide benefit. A litre of olive oil per week was given to those in the olive oil arm of the study, an amount that may cause many dietitians to draw breath. And 210g per week of nuts were provided to those in the nuts arm.

The interventions were designed to enrich diets with foods high in unsaturated fats. How many of us think this way when we educate people about healthy eating?

There are only a few opportunities to build unsaturated fats into people’s diets – vegetable oils, unsaturated spreads, salad dressings, mayonnaise, nuts, seeds and avocado come to mind. Yet much of our ‘healthy eating’ advice in recent years has actively discouraged use of some of these foods: ‘avoid fried foods; use just a scrape of margarine on bread; and choose low-fat salad dressing and mayonnaise’. All of this advice has had the effect of withdrawing protective unsaturated fats from the diet. If body weight management is required the targets for energy reduction should be saturated fat and poor quality carbohydrates, not unsaturated fats. You know, baby, bathwater, etc.

But the low fat dogma runs deep. A challenge for nutritionists is to finally shake it off, relax about percent energy from total fat and undo some of the damage we have done over 30 years with poor advice to the general public about the role of unsaturated fats in healthy diets. The public will love us for it – Mediterranean diets actually taste good.

Image: source

You said yourself the diets differed in legume & fish intake. Both food groups known to have heart protective factors. What would the graph look like with a diet high in these foods but still low in fat?

Quoted “We acknowledge that, even though participants in the control group received advice to reduce fat intake, changes in total fat were small”

The total fat (%) in the control group at the end of 5-years was still 37%… i’d hardly say this was a low fat diet

Yes, they had problems trying to get people in the control group to stick to a low fat diet and had to intensify efforts to increase adherence to it. But did you note that the results with the Mediterranean diets were more impressive after this point of the trial than before? Bill

Hi Kate

To my mind the key issue here is not high/low fat. It’s all about quality of fat and quality of carbohydrate. If carb quality is high then a high carb/low fat may be fine (but the typical carbs in a western diet are equivalent to saturated fat). Similarly, if fat quality is good there is little to be gained from lowering fat intake. Why limit something that’s beneficial? Regards, Bill

Agree totally on the need to put forward positive messages on using mono/poly fats in the diet. In practice, I have significantly changed the cardiac recovery talks I do here to reflect this.

Just on one quote from your blog,

“Based on these findings it would appear that there is little to be gained from choosing polys over monos or vice versa – both appear to be good substitutes for saturated fat (and carbohydrate for that matter). Let’s confine the monos versus polys argument to history.”

On the website (http://www.epccs.eu/home/mediterranean-diet-diminishes-cardiovascular-risk), there is a second graph which shows all cause mortality. On this graph, the EVOO diet shows a lower risk, (hazard ratio of 0.81 compared to control, with the nuts diet at 0.95), but not reaching statistical significance (P=0.11).

While this doesn’t answer a poly vs mono question, in that it doesn’t reach statistical significance, I don’t think we can consign the poly vs mono argument to history. Maybe we still need more trials, or larger trials to see if there is a difference.

Hi Paul. The weight of evidence still favours polys but when you look at macronutrients and CHD risk they now fall into two groups – saturates and carbohydrates in one group and polys and monos in the other, with the latter group being protective relative to the former. I guess I should have said ‘for practical purposes’ there is little to be gained from choosing polys over monos. The thing for nutritionists to get their head around is the equivalence of saturated fat and carbohydrate. Regards, Bill.

Bill, you say that the weight of evidence still favours polys. I should be interested in you comments on this study: Use of dietary linoleic acid for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease and death: evaluation of

recovered data from the Sydney Diet Heart Study and updated meta-analysis

BMJ 2013;346:e8707 doi: 10.1136/bmj.e8707

Hi Anne.

I (and many others) have concerns about the interpretation of this 40-year old Australian study. The intervention is said to be the replacement of saturated fat with polyunsaturated fat, and the outcome was adverse. However, use of Miracle margarine was central to the intervention. In circa 1970 Miracle margarine contained about 15% of fatty acids as trans fats, so the intervention was actually replacing saturated fats with polyunsaturated fats and trans fats. Trans fats have a strong adverse effect on the risk for coronary heart disease and it is highly likely that the adverse effect observed with this intervention was due to trans fats, not polyunsaturated fats. If the original researchers had had there wits about them they might have identified trans fats as a problem in 1970 rather than leave it to others 20 years later.

However, rather than making decisions on the basis of a single trial, I suggest we look at all the good trials together. Have a look at the meta-analysis I quoted in my blog, conducted by Harvard. It shows that replacing saturated fat with polys lowers coronary risk.

Also, we have to consider other lines of evidence. The evidence from prospective studies shows polys are beneficial with respect to saturated fat. The same goes for the studies into effects on blood lipids. And long-term feeding studies in primates show the same. This is rare consistency in various lines of evidence.

I’ve always thought the data for polys was stronger than for monos – just no primary prevention trials with monos – but the recent trial has help to boost monos claims. Regards, Bill

Hi Bill,

In the original meta-analysis of RCTs by Ramsden and colleagues, the authors had similar TFA-related criticism of the studies included in the Harvard meta-analysis. Wondering if you had any thoughts on this?

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21118617

“Both the AHA Advisory(1) and the Mozaffarian et al.(7)

meta-analysis of RCT imprecisely contend that they evaluated the effects of replacing SFA with PUFA, despite the inclusion of the ODHS and other RCT where experimental diets displaced large quantities of TFA-rich partially hydrogenated oils. Indeed, experimental diets replaced common ‘hard’ margarines, industrial shortenings and other sources of TFA in all seven of the RCT included in the meta-analysis by Mozaffarian et al.(7).”

Ramsden, et al tried to account for TFA as well as omega-3 intake in their meta-analysis, which according to my understanding no other meta-analysis has done.

But I agree with your point that we should also consider non-RCT evidence, which on the whole seems to favor polys.

Hi Will

Regarding trans fats, I think the least we can ask of those assessing these studies is that they be consistent. On the one hand, Ramsden et al argue that the Finnish study (which showed the greatest benefit of replacing saturated fat with polyunsaturated fat) was confounded by trans fats and therefore should be excluded from their meta-analysis. But on the other hand they know the Sydney study was confounded by trans fats but include it in their meta-analysis nevertheless. Just inconsistent.

The case that the replacement of saturated fat with linoleic acid alone is detrimental rests on three studies – the Sydney study (discussed above), the Rose study and the Minnesota study. The Rose study was tiny, just 28 people in the corn oil group, very wide confidence intervals, etc.

Which leaves the Minnesota study. Everyone knows why this trial failed – it fell apart. Subjects were supposed to follow the intervention diet for five years but the average time was just one year. No lipid lowering trial with diet would be expected to demonstrate a significant benefit after 12 months. Even treatment with Simvastatin took to longer than this to show benefit in the 4S Study. In the Minnesota study, in those who were on the intervention the longest there was a signal of benefit, not harm, yet Ramsden et al fail to mention this point.

Notwithstanding all of the above, Ramsden et al’s meta-analysis actually shows that replacing saturated fat with mixed polyunsaturated fats (linoleic acid, ALA and long-chain omega 3s) lowers coronary risk. This is what the Heart Foundation of Australia and the National Health & Medical Research Council encourages, as does the American Heart Association I believe. So if everyone agrees on this, let’s support it and implement it. Regards, Bill.

Hi Bill nice summary.

What’s your opinion on saturated fats and whether different sources will affect health outcomes differently? For example saturated fat in butter vs a sausage vs palm oil vs coconut oil.

Hi Joe

This is very topical – several people have come to me off-line with similar questions, especially in relation to coconut oil. Rather than commenting briefly now, I might take this one on notice and prepare a separate post on it. Watch this space. Regards, Bill

Great, I’m looking forward to reading your post on this topic Bill. Coconut oil is becoming really popular amongst the health food community and I often wonder about how healthy it actually is given its saturated fat content.