At last week’s Nutrition Society of Australia conference a debate was held on the topic “Fortified foods do more harm than good”. It was a fizzer with those supporting the proposition being unable to mount any serious arguments. A large majority of the audience disagreed with the idea both before and after the debate. But this was a very informed audience with deep knowledge of the rationale for fortification. Among less scientific groups hostility to food fortification appears to be growing. What’s the problem?

‘Tampering with the food supply’

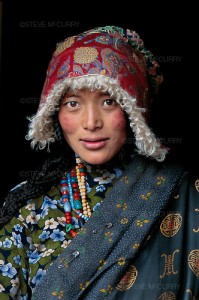

One popular dietary myth is that the consumption of simple, minimally processed foods automatically translates into a healthy diet. As a consequence, any ‘tampering with the food supply’ by faceless scientific types is treated with suspicion and resisted. The defense of naturalism may be logical to a naive audience but it ignores the history of nutrient deficiency in humans. Even today in parts of Tibet a high percentage of the population, consuming a diet of simple, minimally processed foods, suffers from serious intellectual impairment due to iodine deficiency. One of the simplest dietary interventions of all – the addition of iodine to the salt used in food preparation – is all that it takes to solve this crippling problem.

Image: source

Let’s remind ourselves of the WHO/FAO definition of food fortification: “the practice of deliberately increasing the content of an essential micronutrient … so as to improve the nutritional quality of the food supply and to provide a public health benefit with minimal risk to health”. You can see why the debate never went very far. By definition, food fortification does more good than harm.

The use of the emotive word ‘tampering’ in the argy bargy of food activism is intended to steer the fortification debate down a philosophical/emotional path, ensuring that the rationality of science takes a back seat.

Making junk food look good?

One of the recent arguments against food fortification is that it may be applied to junk foods, effectively making unhealthy foods look better than they are. Putting the difficulty in defining junk foods to one side, this argument does not really stand up to scrutiny. Fortification has always been about improving the nutritional properties of staple foods, many of which have been nutritionally poor – junk foods if you like.

A couple of hundred years ago when the cultivation of corn became widespread a peculiar thing happened to the communities that adopted it as the staple of their diet – they got sick. At the time it was thought that corn contained some kind of toxin but the real problem was a deficiency of the vitamin niacin – the people were suffering from pellagra. Early in the 20th century pellagra reached epidemic proportions in the south of the United States and thousands of people died.

Image: source

No modern junk food wreaks the sort of havoc that corn did a hundred years ago. However, once vitamin deficiency was understood and fortification of cereal foods with niacin became routine in modern societies pellagra virtually disappeared. Only after its nutritional shortcomings were overcome did corn shake off its junk status and take its place as a healthy staple food.

If we take the ‘don’t fortify junk food’ argument to its logical conclusion, only healthy foods would be fortified, which is simply wrong-headed. If implemented it would ensure that the only people who would benefit from fortification are those who already consume healthy foods – those that need the benefit the least.

Undermining nutrition education?

Another criticism of fortification is that it undermines nutrition education. This view states that all people should be educated about nutrition; fortification blurs the boundaries of what’s healthy and what’s not-so-healthy; and everyone finds it too confusing. The ambition to educate people about good nutrition drives all dietitians and nutritionists but we need to be careful: establishing education as the only gateway to nutritional health tends to pitch good nutrition at the educated (well nourished) middle class. It does little for the most disadvantaged and the least educated who are more likely to suffer nutritional deficiencies, less likely to be aware of their health problems and less likely seek information or professional help to address them.

The purpose of food fortification is to ensure that the least educated person, living in the most difficult of circumstances, making poor dietary choices by necessity doesn’t suffer a vitamin deficiency disease. It’s a safety net for the disadvantaged and to succeed the foods chosen for fortification need to be the foods that this group chooses to eat.

Case study: Aboriginal people in Bourke

Max Kamien was a man ahead of his time. As a young doctor working with Aboriginal people in the Bourke area of New South Wales in the 1970s Kamien was confronted with their poor nutritional status – more than 30% had clinical signs of vitamin deficiency. Their staple diet was (unfortified) white bread eaten with golden syrup, jam or honey, washed down with large quantities of sweetened tea. This was a junk diet composed almost entirely of junk foods.

Kamien thought the quickest method of improving the health of this disadvantaged group was to fortify their bread with thiamin, niacin and riboflavin. In a forerunner of more recent criticism of food fortification Kamien was attacked in the media for treating the Aboriginal people as ‘the guinea pigs of Bourke’ with his ‘secret bread tests’ (mustn’t tamper with the food supply Max). But within a short period of time, blood levels of B vitamins in the Aboriginal people increased and physical signs of deficiency virtually disappeared. This simple strategy cobbled together by a doctor and the local baker involved no education, just the fortification of a staple food of the target population. And it worked.

The complacency of success

Anti-food fortification arguments are a bit like arguments against vaccination. The success of both public health strategies is so profound and so well established that the wellbeing they create is assumed to be the norm. Complacency sets in, followed by ill-informed questioning of the worth of these public health initiatives.

Maybe we need a good old fashioned pellagra epidemic to remind us why we fortify foods with essential nutrients.