High fat, calorie-rich foods have long been thought to be fattening and policymakers continue to recommend their restriction in order to prevent obesity. However, scientific support for this advice has fallen away. The latest research suggests that identifying foods that promote future weight gain is much more challenging than previously thought, with carbohydrate quality playing a central role.

Traditional dietary advice for preventing obesity has revolved around eating less calorie-rich food. In the 1980s and 1990s the best way of achieving this was thought to be by limiting total fat intake and this became the core strategy for the prevention of obesity. It made good sense as gram-for-gram fat contains more calories that protein or carbohydrate – lower fat foods are lower calorie foods. By the turn of the century, dietary advice for obesity prevention evolved to limiting intake of ‘energy dense’ (calorie dense) foods. This was a small change in emphasis as the key drivers of energy density are fat and water content.

Lowering the fat content or energy density of the diet as a means of preventing obesity makes so much sense to nutritionists and dietitians that it is seldom challenged but the unfortunate reality is that these recommendations can no longer be supported scientifically.

Changes in diet and weight gain

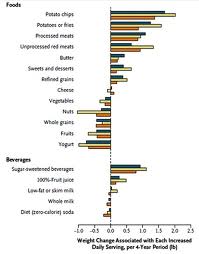

A challenging paper assessing the effects of dietary changes on future weight gain appeared in the New England Journal of Medicine last year. The researchers assessed data from three large prospective cohort studies conducted in the United States, with a total of nearly 121,000 men and women, in order to assess how increased intakes of specific foods affected weight gain over time. The results were similar across the three cohorts, increasing confidence in the validity of the findings, but they were at odds with convention thinking.

Most of the foods that were positively associated with weight gain were not energy-dense or high in fat; they were rich in starch or refined carbohydrates (see Figure 1). Potato, both fried and boiled, was one of the foods most strongly associated with weight gain. Refined cereal foods were also associated with weight gain, irrespective of whether the carbohydrate they contained was in the form of starch or added sugar. Among beverages, both soft drinks and orange juice (lower fat, lower nutrient density) were linked to increased weight gain whereas whole milk (higher fat, higher energy density) was not. Increased intake of nuts, high in fat and energy density, was actually protective. The fat content of dairy products was unrelated to future weight gain, with low fat milk, full fat milk and cheese all having similar, neutral effects. And yoghurt was protective.

Figure 1: source

Nutritionists can take heart that some aspects of current dietary advice for obesity prevention were supported by the study e.g. increased intake of wholegrains, nuts, fruits and vegetables (excluding potato) were protective against weight gain. The researchers suggested that the higher fibre content and slower digestion of these foods may augment satiety, providing a plausible mechanism explaining the findings. It was also suggested that the consumption of rapidly digested starchy foods may be less satiating, increasing hunger signals and total calorie intake. The associated press release highlighted improving carbohydrate quality as one of the most useful dietary metrics for preventing long-term weight gain.

With refreshing frankness the researchers concluded that Our findings highlight gaps in our mechanistic understanding of how dietary characteristics alter energy balance. They stated that Several dietary metrics that are currently emphasised, such as fat content, energy density and added sugars, would not have reliably identified the dietary factors that we found to be associated with long-term weight gain. Unfortunately, these metrics continue to be seen as relevant to obesity prevention by policy makers in Australia today.

Image: source

Energy density: past its use-by date

The failure of energy density to predict future weight change in the US study should not have come as a surprise. The energy density hypothesis was based on a questionable assumption i.e. that humans eat the same weight of food each day, so eating energy dense foods leads to ‘passive overconsumption’ of calories. However, the hypothesis was based on the findings of short-term studies lasting less than five days. Better, longer-term studies are now available.

The role of dietary energy density in weight change over time has now been assessed in six prospective cohort studies but they provide little support for the hypothesis. The largest and most recent of these – the EPIC study – found no association between energy density and weight change after 6.5 years of follow-up. Another publication from the EPIC study found that fat intake was not associated with weight gain, the authors concluding with These findings do not support the use of low-fat diets to prevent weight gain.

The best test of a hypothesis is the randomised controlled trial and three relevant trials have been published (discussed in a recent review). All were cancer prevention trials using low fat diets, high in fruits and vegetables i.e. low energy density diets. After between 4 and 7.5 years, mean body weights in the intervention groups were less than one kilogram above or below those in the control groups in all three studies. In other words, the effects on body weight of years on a low energy density diet were negligible.

It would appear that people adapt to a low energy density diet by increasing food intake in the medium term, presumably due to regulatory mechanisms driven by calorie requirements. When you think about it, it would be very strange if humans could not adapt to different food environments.

Fat, energy density and the draft Dietary Guidelines

No association between dietary fat and obesity was found in the systematic literature review conducted for the Australian Dietary Guidelines currently under development. Unfortunately, no review of energy density and obesity was conducted. Despite the total lack of an evidence base, the draft Guidelines stated that Reducing the amount of dietary fat will not necessarily reduce dietary energy, but it is prudent to choose low fat and low energy density foods …

Since when is it ‘prudent’ for public health nutrition policy to be based on no evidence? Obesity prevention based on lowering fat intake and energy density is a good example of dietetic dogma – beliefs deeply held by nutritionists that are no longer supported by science. It’s to our discredit that we can’t respect our science, admit past mistakes and modify old dietary messages that we know to be wrong.

Low fat foods certainly are less filling and even more so if the food is medium-high GI. Thus, a person tends to feel more hungry, or perhaps even ‘give in’ to more of these low fat foods just because they’re “safe”. In terms of calorie content, I think it depends on the quality of those calories. Of course a food can be low in fat and still be high in calories (from extra amounts of sugar and other forms of carbohydrate, to make up for the taste/texture). There needs to be a balance in the diet – if a diet is low in fat and calories, it may only work for so long, until the body adjusts to it and doesn’t change anymore, and the person stops losing weight or may even start gaining weight. I think it’s useless when people obsess about how much fat or calories there are in certain foods, and avoid them like the plague. Eating a balanced diet with a combination of high and low calorie, and high fat and low fat foods is more satisfying and easier to adhere to in long term.

A voice of reason. Cheers, Bill

Bill, what do you think about this?

http://wholehealthsource.blogspot.com.au/2012/06/calories-still-matter.html

Hi Bill,

I really enjoy your blog and challenging the dietetic dogma as you describe it, trying to report the evidence and integrate it to practice.

From this paper are you suggesting that if the quality of the calories ie from nuts, dairy, fruit, whole grains and unprocessed meats exceeded the estimated energy requirements of an individual they would be unlikely to gain any or significant weight?

Would the same aply if they were trying to lose weight?

I agree that recommendations without the evidence to support it is futile and maybe there are PhDs needed to review this evidence.

How do you see your interpretation of the literature being considered in our current nutritional recommendations?

Keep up the good work.

Regards

Hi Peta

The authors of the paper I reviewed are clear that all calories count and that any effect of individual foods on weight gain over time must work through changing energy intake. It would appear that the effects of different foods on hunger and satiety may be a key issue. If X calories from Food A are more satisfying that X calories from Food B, you would expect Food A to be associated with less weight gain in the long term. The effects of carbohydrate-rich foods on insulin levels after meals could well turn out to be a key factor.

I have no faith that any of this will be taken up by those developing our current dietary guidelines. The process is very ideologically driven. On one side you have conservative nutritionists who just can’t bring themselves to change long-held views, even though they no longer stack up scientifically. And on the other side you have a group that is more interested in global warming. Environmentalism is important but I just don’t see it having a role in advice about diet and health. The issues are separate.

Nutrition science is at a low ebb in Australia. Regards, Bill

Bill,

The results of the study didn’t come as a surprise to myself.

One the ‘low fat’ question. I think where the guidelines also need to be careful is how the ‘low fat’ message is interpreted by the public. Can having this message in the guidelines further encourage people to look for “low fat” on processed foods? This study (published in a marketing journal) found when a product was labelled ‘low fat’, consumption increased.

http://foodpsychology.cornell.edu/pdf/permission/2006/LowFat-JMR_2006.pdf

As well as lacking in evidence, does the promotion of ‘low fat’ have other negative effects?

Hello Paul. Yes, promoting ‘low fat’ has a couple of negative effects. Firstly, if unsaturated fats are preferentially reduced in the diet it would be expected that the risk for coronary heart disease would be increased. Secondly, if carbohydrate takes the place of fat in the diet there may be different consequences for different types of carbohydrates. If the carbohydrate is high fibre/low GI/nutrient-dense – fine, but if it is low fibre/high GI/nutrient-poor nutritional status would be reduced and risk would increase.

I can see no reason for recommending low fat diets – they are a hangover from another era. It’s better to advocate that people eat good fats and good carbohydrates. Regards, Bill

Hi Bill,

I understand entirely where you are coming from when you say the environment and nutrition are separate issues. But are they? I do think that the guidlelines should show an optimal diet, but seeing as it is a national set of guidlines which is widely used, do we not have a responsibility to make sure people know that we won’t be able to acheive it forever more? Although I’m not up to date on the latest, fish is the first one that comes to mind. Perhaps a disclaimer is needed on the optimal diet to explain these things.

On top of environmental factors are economic factors. Do we not need to take them into account? For example, *if* organic fruit and vegetables were shown to provide better nutrition than conventional produce, would we put that on the DGAs, seeing as they would then be shown to provide ‘optimal’ nutrition?

Hi Jenna

The core business of the Dietary Guidelines is to review the latest nutrition science and to develop guidelines consistent with that science. But when the first document from the Australian Dietary Guidelines process was circulated it was obvious that environment had been placed first and nutrition second. The document identified iron as a marginal nutrient and then restricted red meat serves; it identified calcium as a marginal nutrient (adolescent girls) and then restricted dairy serves; it recognised that vitamin D deficiency was a growing problem in Australia and then restricted ALL major dietary sources of vitamin D – all on environmental grounds.

What shocked me was how willing those responsible were to compromise nutrition for the sake of the environment. If nutritionists don’t defend nutrition, who will? It’s our job! Regards, Bill

Thanks for this opinion review/blog. Is good to see how the science is stilling being kept to the forefront of advice or potentially in many cases not. I don’t think many dietitians would dispute the case of the carbohydrate issue – in terms of quality and quantity especially in the backdrop of ever increasing rates of insulin resistance/T2DM. I have come to appreciate that from clinic work the likeliness of an overweight patient actively listening after the mention of ‘low fat’ diet or even ‘calorie restriction’ is slim to none. I think it would be really useful and interesting if more work was done to monitor and review outcomes if dietetic intervention was compared i.e low fat/low calorie vs low GI/high fibre or are there studies already out there? This may help move policy/recommendations along but ultimately also ensure the most beneficial info is provided.

Personally I tend to advocate for low GI (to aid satiety) whilst promoting the Mediterranean diet (good fats and higher fibre). In essence it has to be a lifestyle change and this doesn’t necessarily equate to counting exact calories or grams of fat for the negative effects already mentioned.

Hi Tim. I think your low GI/Mediterranean approach is soundly based. I guess I might add higher protein as another means of keeping the glycaemic load down.

There have been some comparisons of nutrition interventions, such as the Diogenes study mentioned in a recent blog. I’ll cover some other interventions in future blogs. Regards, Bill

Hi Bill

Another great article that really challenges my thinking love it.

Can you talk about satiety and GI some time soon? Is fuller for longer evidence based?

Thanks Duncan

It is simply maddening that public policy and nutriton education is still using the low-fat mantra as the core component to educate and inform. I am about to put out a series of emails that must use the govt guidelines to inform staff. The basis of which is low-fat. Aaargh this system is so flawed. I am currently completing my masters and if we don’t use the low-fat guidelines in answering questions and nutrition care plans we are marked down.

Awesome. Thanks for posting that. I’ll definitely come to your site to read more and tell my coworkers about it, hcg.