Addressing the obesity epidemic by taxing sugary soft drinks sounds good in theory but it appears to fall down in practice. How could a taxation strategy be made to work?

Obesity is proving to be an intractable public health problem demanding innovative solutions and one idea that is attracting attention is the taxation of sugar-sweetened beverages. The theory is simple enough. Basic economics tells us that if the price of sugary soft drinks were to rise, their consumption would fall; lower intake should mean lower calorie intake which would lead to lower body weights. But would it work in practice?

The Ohio experience

A recent research study conducted in the United States provided some interesting insights. Taxing soft drinks has a long history in the US and occurs in many states today, though historically the rates have been low and the purpose has been to raise revenue. But there was an interesting exception. In 1992, the state of Ohio introduced high taxation of sugary soft drinks which was then repealed at the end of 1994. This provided an opportunity to test the effect of taxation of soft drinks on body weights over a period of two years. The researchers compared changes in body weights in Ohio over this period to (1) all other states that had no increased taxation and (2) a bundle of states with the same mean BMI as Ohio. The researchers found:

… very little evidence that the large tax imposed in Ohio had any detectable effect on population weight … our results cast serious doubt on the assumptions that proponents of large soda taxes make on its likely impacts on population weight.

How come? Why didn’t quite high taxation of sugary soft drinks affect body weights?

How strong is the evidence that soft drinks affect body weight?

It may come as a surprise to many dietitians and nutritionists that there is actually a debate in the scientific literature about whether lowering intakes of sugar-sweetened beverages would reduce the prevalence of obesity. Two excellent papers published in Obesity Reviews last year presented the opposing views.

In one corner was Professor Frank Hu from the Harvard School of Public Health who argued that the issue of whether sugary soft drinks are linked to body weight has been resolved and the answer is yes. In developing his argument Professor Hu first drew on epidemiological studies, citing a Harvard meta-analysis of cohort studies. It has to be said that the association between sugar-sweetened beverage consumption and body weight in children in this study only just reached statistical significance, though an updated meta-analysis by the same research team is also supportive.

The second line of evidence considered was randomised controlled trials, which would be expected to provide better insight but these were relatively few in number and their findings were conflicting. However, Professor Hu was swayed by two recent high quality trials by Ebbeling et al and de Ruyter et al both of which indicated that sugary drinks affect body weight.

Image: source

The alternative view

The alternative view was presented by a team headed by Professor David Allison from the Nutrition Obesity Research Centre at the University of Alabama. Their view was based on data from their updated meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials, which included the two recent trials by Ebbeling et al and de Ruyter et al. Again the trial evidence was equivocal. On the one hand, adding sugar-sweetened beverages to subjects’ diets was linked to increased body weights, but lowering intake of these beverages did not lower body weight, except in overweight subjects. However, these authors noted that the recent high quality trials were ‘tilting the needle’ in favour of an association.

The effect size is small

One thing that had never really registered with me was how small the ‘effect size’ of sugar-sweetened beverages on body weight really is. The authors explained it thus:

Increasing consumption of [sugar-sweetened beverages] explains 1.92% of the variance in body weight or BMI change. Reducing consumption of [sugar-sweetened beverages] in persons of all weight categories explains 0.09% of the variance in body weight or BMI change. Among persons who are overweight or obese at baseline, reducing the consumption of [sugar-sweetened beverages] explains 1.54% of the variance in body weight or BMI change.

So although the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages appears to be linked to body weight the magnitude of the effect is tiny.

Is substitution a factor?

One of the key assumptions of the taxation strategy is that the higher cost of sugary soft drinks would result in lower intake of these beverages and lower calorie intake. In other words, there would be no substitution with other calorie-containing drinks or foods. This may well be the case in the constrained environment of a randomised controlled trial but would it happen in real life?

A study in 2010 found that although taxing soft drinks resulted in a small fall in soft drink consumption this was completely offset by increases in consumption of other high calorie drinks, such milk-based drinks. Consequently there was no effect on total calorie intake at all. Although most nutritionists would be glad to see nutrient-rich beverages replacing nutrient-poor drinks in children’s diets, this is not the intended purpose of an obesity tax.

Could taxation be made to work?

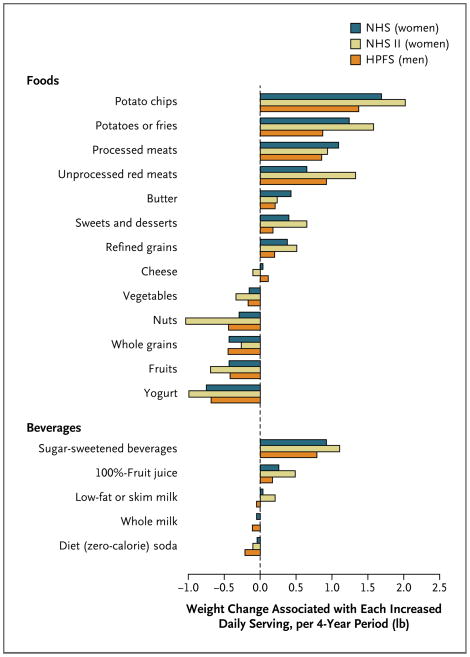

If taxation is to work as a strategy for obesity prevention it may be worthwhile revisiting the 2011 study by Mozaffarian and colleagues which looked at which foods and drinks were associated with weight gain over time. The surprising findings of this study, which considered three large cohorts of men and women, were that just about every group of foods and drinks was associated with weight gain, positively or negatively.

Image: source

Although sugary soft drinks were positively linked with weight gain, so were fruit juice, potatoes, potato chips, red meat, processed meats, sweets and desserts, butter and refined grains. Rather than tax just one of these, an effective strategy for obesity prevention would probably need to tax them all. As nuts, yoghurt, fruits, vegetables and wholegrains were all negatively associated with weight gain an effective taxation strategy would also need to lower the price of these relative to the ‘fattening foods’ and also those foods with an apparently neutral effect.

Although it sounds complicated it might work. But would the Federal Treasury ever support such an approach?

Very interesting, thanks for the update Bill.

I reckon we should tax foods that provide serious kilojoules without real health benefits – eg full strength soft drinks and crisps, even high fat takeaways would be useful. Red meat is a relatively healthy, fresh, unadulterated food that provides iron, zinc and protein so it could be left out of the basket. If this could then reduce the cost of fresh fruit and vegetables, nuts, seeds etc it might end up having a favourable outcome on the health of the population over time.

Federal Treasury can be as innovative as they want, depending on how they view the potential efficacy of a strategy and how much they want to keep industry happy. Unfortunately I don’t think it will happen soon.

It would be good if they also do something to restrict the upsizing of takeaway foods? Many people buy more than they need to consume because it is ‘economical’ – a quick decision they make at the point of sale as the price difference and immediate efficiency is obvious.

I think it’s a cop out to argue that we are all in control of our purchases and that advertising, pricing and other sales strategies have no impact – sure, that’s currently working really well

Hi Jayne.

I don’t think it will happen soon either. The current government will say it’s ‘nanny state’ and it’s adding more complexity to the tax system when more simplicity is required. The Federal Treasury will say that if there is no revenue in it, what’s the point?

Has anyone else got any good ideas about how to tackle obesity?

Regards, Bill