Limiting saturated fat intake has been recommended for decades as a way of lowering the risk for coronary heart disease. However, this recommendation needs to be revised following recent findings that saturated fat and carbohydrate confer the same risk for heart disease. Now the best advice is to replace saturated fat with unsaturated fat.

In the beginning: the Seven Countries Study

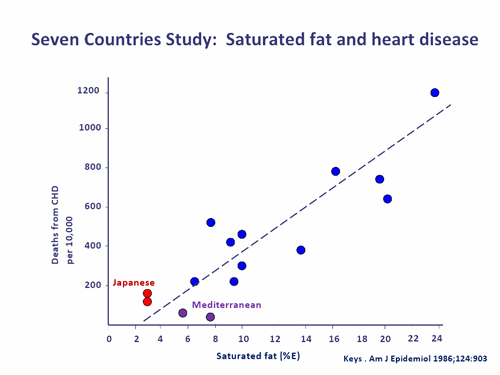

The Seven Countries Study shaped the thinking of a generation of nutritionists. In this famous study the diets in fifteen cohorts of subjects in seven countries were examined and the risk for various diseases was estimated over time. The most compelling finding was the positive association between dietary saturated fat and the risk for coronary heart disease – the lower the intake of saturated fat, the lower the risk for heart disease.

Image source: Redrawn from Keys et al. Am J Epidemiol 1986;124:903

Importantly, it didn’t seem to matter how a low saturated fat intake was achieved. In some Mediterranean countries where olive oil was used extensively, saturated fat was effectively replaced by monounsaturated fat – the diets were moderate or even high in total fat. The rice-based diets in Japan were very different – saturated fat was effectively replaced by carbohydrate and total fat intakes were very low. Two models of healthy eating were born, both focussed on lowering saturated fat intake, but as concern about total fat intake increased in Australia and the United States the low fat, low saturated fat diet became the recommended diet.

The paradigm shifts

The simple story suggested by the Seven Countries Study started to unravel when large prospective cohort studies conducted in single countries, with subjects from similar socioeconomic backgrounds were commenced. These studies were designed to limit the likely confounding at play in cross-cultural comparisons such as the Seven Countries Study. In 2005, the 20-year findings of the Nurses’ Health Study, conducted in the United States, were published and confirmed the study’s earlier findings that the risk for coronary heart disease associated with eating saturated fat and carbohydrate were similar. Polyunsaturated and monounsaturated fats were associated with lower risk.

There was always the possibility that the Nurses’ Health Study findings reflected an American phenomenon so there was great interest in a recent pooled analysis of 11 European and US cohort studies. The results – the coronary heart disease risk associated with saturated fat and carbohydrate were the same. The best reduction in heart disease risk occurred when saturated fat was replaced by polyunsaturated fat.

All nutritionists should read this study and contemplate its implications.

The low fat diet is dead

The most important implication is that the low fat diet is dead, at least as a strategy for preventing heart disease. If saturated fat and carbohydrate confer the same risk for heart disease there is nothing to be gained by swapping one for the other. Low fat diets may actually increase the risk for heart disease if unsaturated fats are displaced by carbohydrates.

For some nutritionists, the demise of the low fat diet actually occurred in 2006 with the publication of the Women’s Health Initiative, the largest randomised controlled dietary trial ever conducted. Nearly 49,000 United States women participated in the study into whether a low fat diet affected the risk for major cancers and cardiovascular disease. Risk for myocardial infarction and stroke was unaffected after eight years on the low fat diet. So neither randomised controlled trials nor cohort studies support a protective role for low fat diets against heart disease.

Replace saturated fat with unsaturated fat

‘Limit saturated fat’ is no longer evidence-based advice as it implies that saturated fat can be replaced by anything – carbohydrate, monounsaturated fat or polyunsaturated fat – and benefit will follow. If carbohydrate is not a beneficial replacement, the advice needs to become ‘replace saturated fat with unsaturated fat’ and this is the approach adopted in the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (2010). As one type of fat is replacing another, the recommended fat content of heart healthy diets is now moderate, not low.

Image source

So the Mediterranean-type diet has won the day, though the concept needs to be broadened to include polyunsaturated fats which may turn out to be the ideal replacement for saturated fat. The benefit of replacing saturated fat with polyunsaturated fat was confirmed by a recent meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. The authors argue that the limit of 10% of energy that is sometimes suggested for polyunsaturated fat intake is not evidence-based. There is precedent for high polyunsaturated, low saturated fat diets e.g. the Taiwanese diet where soybean oil – ‘the olive oil of the East’ – is widely used and coronary heart disease rates are low.

Dietary Guidelines

Don’t expect to find any of these important findings in the new Australian Dietary Guidelines because, inexplicably, the evidence linking saturated fat with coronary heart disease was not even reviewed. The expertise to interpret the new evidence was certainly available in Australia. In 2010, leading fats experts Professors Andrew Sinclair and Paul Nestel participated in an international expert consultation on this issue and Professor Peter Clifton discussed it at the recent International Symposium on Atherosclerosis.

We are now confronted with the possibility that the 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans will be up-to-date on saturated fat but the 2012 Australian Dietary Guidelines will not.

Are carbohydrate recommendations too high?

Another important implication is that current recommendations for dietary carbohydrate may be too high. In Australia, the recommended range for carbohydrate intake is 45-65% of dietary energy – a rather high range that was recommended at a time when low intakes of total fat were thought to be beneficial for health. The mean intake of carbohydrates by Australian adults falls on the lower boundary of this range, suggesting that the health of many adults would be improved by the consumption of more carbohydrate. However, feeding more carbohydrate to an increasingly overweight, sedentary, insulin resistant population is not a recipe for health. Eating less carbohydrate and more unsaturated fats would be more beneficial for heart health. Both boundaries of the current recommended carbohydrate range appear to be too high.

Better quality carbohydrates?

Although total carbohydrate is associated with similar heart disease risk to saturated fat, it would be expected that some carbohydrate-rich foods are better than others i.e. that there are good and bad carbohydrates. But carbohydrate quality remains a poorly defined concept. What are the key parameters? Should nutritionists focus on sugars, complex carbohydrates, glycaemic index, dietary fibre, wholegrains or nutrient density?

I’ll be exploring the issue of carbohydrate quality in a series of articles in the coming weeks.

Hi Bill,

2 questions:

1) If the Japanese have traditionally had a low sat-fat diet but high CHO from rice, why are they placed at the lower end of the graph as shown above?

2) How could we communicate replacing saturated fat with unsaturated at a dinner meal, say a typical Australian meal of chops and 3 vegies? Cut the fat off the chops and fry in unsaturated oil/margarine?

Hi Jenna. It is now thought that the Seven Countries Study was heavily confounded i.e. that there were many other factors at play other than just diet or saturated fat, in particular. For example, the populations that were compared included poor, rural Japanese farmers and wealthier, urban Americans – very different. The Japanese were very lean, very active and, presumably, insulin sensitive. Maybe eating a high carbohydrate diet in this context has no adverse consequences. But in modern Western populations – overweight, sedentary and more insulin resistant – carbohydrate appears to be more detrimental.

In relation to practical advice, you can firstly think in terms of replacing saturated fat with unsaturated fat. So yes, your ‘trim the chop, pan-fry with oil’ example works. But there is also likely to be benefit from replacing high GI carbs with unsaturated fats, so having potato cooked in oil would be recommended in preference to an equicaloric amount of boiled potato. Regards, Bill

Great post Bill.

I think there is a danger in how we communicate this message to the public. I can see mass media translating this message into articles titled ‘Saturated fat is ok’. Many people will read an article heading and not the actual content. It is possible that the public will miss the bigger picture and just relax their saturated fat intake instead of swapping for unsaturated fats. As per Jenna’s second question, it is important to be able to follow up with practical advice on the healthiest way to substitute saturated fats and poor quality carbohydrates.

Jaqui, there are already interests at work trying to tell the general public that saturated fat is OK, though nutrition books by non-nutritionists and public relations activity through current affairs programs . We nutritionists need to ensure that the correct message gets through, in sensible food-based advice. One task is to rehabilitate unsaturated fats, which were wrongly targeted during the misguided ‘eat less fat’ period.

Another challenge for nutritionists and dietitians is to get their heads around the concept of carbohydrate quality. Frank Hu from Harvard addressed this topic at some length at a recent symposium in Sydney. We need to re-think past advice e.g. the message in our last Dietary Guidelines to ‘eat plenty’ of foods like rice. Eat plenty of nutrient-poor, high GI carbohydrate was hardly good advice. Regards, Bill

Thanks Bill. Also:

1) Further to article, would you also advocate for full fat soy milk over low-fat or skim dairy milk?

2) I work in remote WA and I suppose that some of the fear of guideline-makers is that unsaturated fats are expensive (nuts, avocado, fish if it’s not caught locally etc) compared to rice and bread, and therefore ideal nutritional intake may not be accessible to lower SES groups. What are your thoughts on that?

3) What’s your view on how to handle the people who say their cholesterol has greatly dropped and they use 2kg of butter a week etc, eg. the story on Today Tonight or whichever show it was a couple of weeks back. Do you feel that this is more likely due to the drop in CHO intake rather the the fact they’re using butter? Recently a dietitian was telling me about some nutrigenomics papers that suggested there are particular people with genes that benefit from low fat but others that benefit from low CHO in regards to diet.

Thanks for your articles and look forward to more.

Hi Jenna

1. In practice I don’t think I would discriminate between full fat soy milk and skim dairy milk. But theoretically the soy milk would have a better effect on the ratio of unsaturated to saturated fats than the skim milk, so I guess it would be preferred. Last time I looked the fat in soy milk was predominantly sunflower oil.

2. Unsaturated fats include canola and sunflower oils, which are inexpensive. However, a healthier diet and a cheaper diet are two different things and there are inevitable compromises when working with low SES groups.

3. The idea of eating huge amounts of butter and having your blood cholesterol go down is the sort of thing that you hear about on Today Tonight but don’t read about in scientific journals. Ignore Today Tonight and read Mensink RP et al. ‘Effects of dietary fatty acids and carbohydrates on the ratio of serum total to HDL cholesterol and on serum lipids and apolipoproteins: a meta-analysis of 60 controlled trials’. Am J Clin Nutr 2003;77:1146-55.

This story has some nuances that are still to be explored – I look forward to your upcoming articles. Prospective studies have shown whole grain intake to be protective against cardiovascular disease independently of saturated fat intake. Therefore, limiting saturated fat as well as sugar and refined grains should still be sensible advice.

Thanks Robert. There are many nuances to carbohydrate quality – it’s not a simple concept. The potential parameters include wholegrains, dietary fibre, sugar, starch, GI and nutrient density. And there are contradictions e.g. some wholegrains are quite nutrient-poor and have high GIs. Are they good? In the weeks ahead I’ll be looking at the issue of carbohydrate quality in a series of articles. I look forward to your contribution to the debate. Regards, Bill

Bill, I am enjoying your posts immensely. Good stuff!

Just interested in your thoughts (on what i often think), the way nutritional science which leans to a ‘reductionist’ approach focuses us too much on the nutrient and not more on also taking the step back to acknowledge the whole food matrix and complex synergy that can occur between all food components ( nutritive and phytochemicals).

There is an evidence base emerging around particular ‘saturated’ fat foods nutritionists advise to limit such as dairy and coconut oil where as foods observational research supports they are associated with lower risk of CVD. I admitedly have not read up all the research but there is some saying there are many different types of saturated fat which all have varying effects on the body and that the entire nutrient composition of a food may be more important than concentrating just on the type of fat?

I was wondering if you have read into this and could comment and your thoughts or others on whether a pointer for us is not to still focus mainly on talking to nutrient recommendations but to foods more? This is also of relevance where consumer research often shows consumers are really confused on ‘nutrient’ terminology.

Hi Jutta. I hope my answer doesn’t disappoint you. Nutrition science IS reductionist and always will be. But that’s not a bad thing.

It’s not enough for nutritionists to note that Food A appears to be protective against Disease B in a prospective cohort study and then just assume that the association is causal. Rather than Food A being particularly healthy, it may be that healthy people tend to eat Food A. You never know from a cohort study.

The question that always has to be asked is: what plausible mechanism could explain this association? If a food is having a real effect then something is being up-regulated, or down-regulated, or blocked – something is happening in the body that results in the protection. Yes, this is all very reductionist, but essential to demonstrate that the effect is real. If there is no plausible mechanism, we need to be cautious about promulgating the advice.

There may well be a ‘complex synergy’ of nutrients and phytochemicals that affects health. But if you can’t explain it scientifically it’s just an assumption. I’m anti-mythology. If our recommendations can’t stand up scientifically, I don’t think we should make them. There are plenty of sound reasons for making dietary recommendations so why introduce some less-than-sound reasons?

Currently there is a lot being said about food-based dietary advice, but surely all advice to the general public should be food-based. However, I would be concerned about a nutritionist who only thought in these terms. It would mean that they never ask the question: Why is it so? How does it work? Regards, Bill

Hi Bill, You say “…the best advice is to replace saturated fat with unsaturated fat.” The meta-analysis you cite speaks only to risk reduction in the Methods and Findings paragraph but then in the Conclusions paragraph says, “These findings provide evidence that consuming PUFA in place of SFA reduces CHD events in RCTs.”

I’d like to call your attention to another article entitled “Dietary fat quality and coronary heart disease prevention: a unified theory based on evolutionary, historical, global and modern perspectives.” The full text of this 2009 article can be accessed here: http://thepaleodiet.com/published-research

Excerpt from page 7:

“Traditional Mediterranean, rural Japanese, and other populations with

very low CHD risk have uniformly low LA intakes [26,32]. Two US

prospective cohort studies have reported inverse associations between

LA intake and CHD risk [41,66]. However, because LA intake was

uniformly high, severalfold higher than evolutionary intakes and those

of modern groups with very low CHD rates [32], these studies provide

little insight into optimal LA intakes. Moreover, both studies relied

on food frequency questionnaires, which have well-known limita-

tions [67] and may not be able to disentangle the effects of LA and

n-3 ALA. Controlled trials in which high-LA oils replaced TFA- and

SFA-rich fats have shown conflicting results [38,68–72], despite the

fact that LA was accompanied by large amounts of medium- [38,70]

and long-chain n-3 PUFAs [38]. A single small trial testing the specific

effects of LA without n-3 PUFAs found increased CHD risk [71].

The only long-term trial that reduced n-6 LA intake to resemble a

traditional Mediterranean diet (but still higher than preindustrial LA

intake) reduced CHD events and mortality by 70% [31]. Although

this does not prove that LA intake has adverse consequences, it clearly

indicates that high LA intake is not necessary for profound CHD

risk reduction.”

I have personally experienced the damaging effects of prolonged high omega-6 lenoleic acid consumption. Fortunately, in late 2009 watched this video http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dgU3cNppzO0 of Dr. Bill Lands discussing omega-6. When I heard him say that “…each 28 gram, one ounce serving of peanuts contains 4,000 milligrams of omega-6 and one milligram of omega-3,” I realized my mistake. I stopped eating peanut butter sandwiches for lunch and within two months my leg pains subsided. I have since regained considerable strength and stamina and my gingivitis has cleared up. I have been researching the omega-6 hazard ever since.

I finds it disturbing that the Harvard School of Public Health recommends saturated fats be replaced by omega-6s on the basis of an assumed risk reduction that supposedly translates into a reduction in cardiovascular events.

Thanks for your comment David. I hear this argument frequently and I’d like to highlight a few issues with it. The claim that linoleic acid intake in the United States is ‘severalfold higher than evolutionary intakes and those of modern groups with very low CHD rates’ is not true. When I first heard this claim in the mid-1990s I thought surely there was a hunter-gather diet that was based on nuts and it didn’t take long to find the !Kung Bushman in southern Africa whose dietary staple was the mongongo nut – high in linoleic acid. The diet of the !Kung was very high in fat and polyunsaturated fat. These people were renowned for their lack of heart disease and longevity.

At the same time I found a comparison of the United States and Taiwanese diets, conducted by Ernie Schaefer and others from Tufts. The ubiquitous soybean oil in the Taiwanese diet gave rise to a moderate fat, high polyunsaturated fat diet – the content of PUFA was much higher than the United States diet. The blood lipids levels and coronary heart disease rates were better in the Taiwanese. So when dietary stories are told it’s always useful to dig into the literature and see if they hold true.

The Harvard position, recommending the replacement of saturated fat with polyunsaturated fat, is based on their data from three large prospective cohort studies and its consistency with randomised controlled trials, mechanistic studies and long-term feeding studies in primates. You can’t find this sort of consistency for any other macronutrient exchange. The World Health Organisation, the American Heart Association, the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, the Australian Heart Foundation, CSIRO and the Baker IDI Heart and Diabetes Institute all generally support this position, so Harvard is in good company. Regards, Bill

salutations from over the world. excellent blog I will return for more.

I appreciate your helpful writing. topnotch work. I hope you write others. I will continue watching

Very interesting info!Perfect just what I was searching for!

I reckon something genuinely interesting about your web blog so I bookmarked .

Interesting^^

I view something genuinely interesting about your web site so I saved to fav.

This site was… how do you say it? Relevant!! Finally I’ve found something that helped me. Kudos!

I see something truly interesting about your web blog so I saved to favorites .

This writing has inspired me to start writing on my own blog

I Will have to come back again when my course load lets up – nonetheless I am taking your Rss feed so i can go through your site offline. Thanks.

salutations from over the sea. interesting article I will return for more.

This blog has inspired me to carry on focusing on my own blog

Rattling good information can be found on this blog.

I think fat is very important in the diet. I would never count or obsess about how many grams of fat I’m getting in my diet, as long as I know what I eat is generally healthy, then my fat intake is most likely no problem. I don’t avoid saturated fat like the plague anymore. In fact, a high carbohydrate diet with almost zero fat can be harmful in long term I’ve read. Especially if those carbohydrates are from low-medium GI, replacing all the fat in the diet, which can cause insulin levels to rise more easily, high triglycerides and dyslipidemia. Even if those carbohydrates eaten are of mostly whole-grains, I still think it’s very unbalanced to have a diet that’s basically very low fat and high in carbohydrates. GI sure plays a role, but what is the cut-off point of that? If we all went on a diet high in complex carbohydrates, would that magically just solve our diabetes, cardiovascular, and basically the metabolic syndrome issues? I’m not 100% convinced. So yes, fat is very important in the diet and I just wish the majority would stop obsessing so much about how “bad” it is.